Blockchain: A House Divided

Is this burgeoning technology overhyped or underestimated?

It seems like everyone is talking about Blockchain these days, but the tenor of the conversation varies dramatically. On the one hand, there are those who proclaim that blockchain (aka distributed ledger) is – or is fast on its way to becoming – the most influential technological marvel to hit the market since the commercialization of the Internet. Others contend that blockchain is more like a Shakespearian tale: “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Like most highly divisive topics, the odds are the reality rests somewhere between the two extremes, but since the stakes of coming down on the wrong side of this issue have the potential to be very high, let’s take a look at both perspectives.

PKI 2.0?

First, we have naysayers like Luther Martin, a technologist with Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s Data Security organization. Martin has referred to blockchain as “the PKI of the 21st century.” Ouch. The much-hyped PKI (public-key infrastructure) encryption protocol was designed to secure the transfer of Web-based information. Though it found limited success in some niche areas, like certain government implementations (Defense Information Systems Agency), PKI has largely been deemed too complicated, too expensive and too vulnerable to breaches. “PKI ended up having just a few useful applications and disappearing into the IT infrastructure in a decidedly non-flashy way, we’ll probably see the same thing with blockchain technology,” Martin has noted.

Hewlett Packard Enterprise technologist Luther Martin says blockchain is “the PKI of the 21st century.”

Speaking at the D+H Insights conference in New York earlier this year, Ryan Zagone, Director of Regulatory Relations for crypto-currency firm Ripple also feels that the hype around blockchain is overblown. “It felt like blockchain would fix every financial problem and cure Zika along the way.” Instead, he noted, there are many examples of blockchain implementation that have fallen well short of expectations. In Vermont, for instance, Zagone explained that a program to implement blockchain for a public records management system was scrapped when it was determined that the cost of the implementation would outweigh any potential benefits. The singular advantage, according to the report, would be attracting companies that use the technology to the state.

The Vermont case proves, according to Zagone, that “you can’t throw it [blockchain] at everything.” Blockchain works best, Zagone said, where “the technology suits the right problem.”

Supply Chain Success

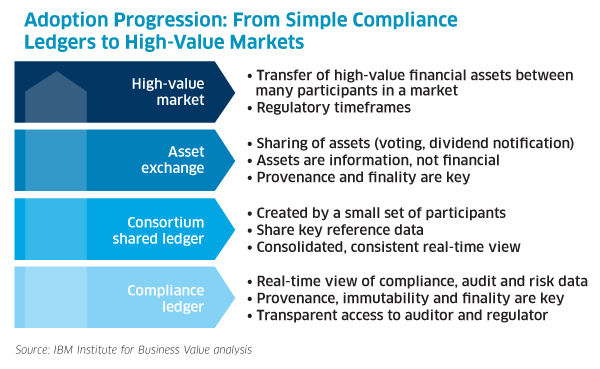

Many proponents of the technology say that there are, indeed, a wide variety of problems that blockchain can solve. A scan of recent headlines demonstrates the vast range of potential applications from the more obvious finance use cases to reducing carbon emissions, combatting money laundering, healthcare, food safety and even trade in legal marijuana to several supply-chain specific applications including smart contracts and product provenance. In fact, Jerry Cuomo, IBM’s Vice President for Blockchain, believes that supply chain is second only to financial services as the most likely application of blockchain technology.

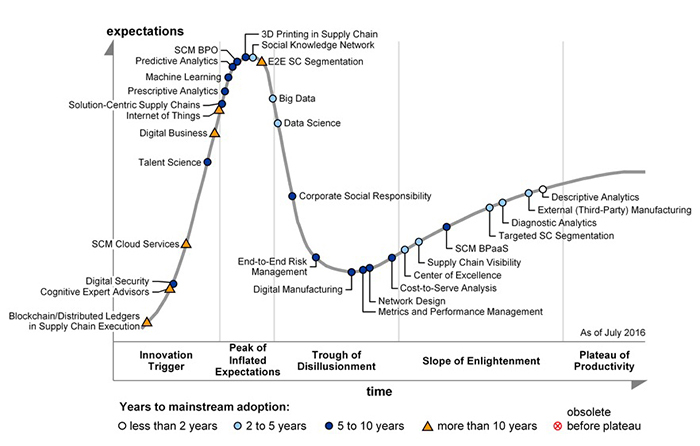

And though research firm Gartner Inc. places blockchain at the very earliest stage of their “Hype Cycle for Chief Supply Chain Officers, 2016” – meaning mainstream adoption is likely at least a decade away – early success stories demonstrate that blockchain is already proving transformative.

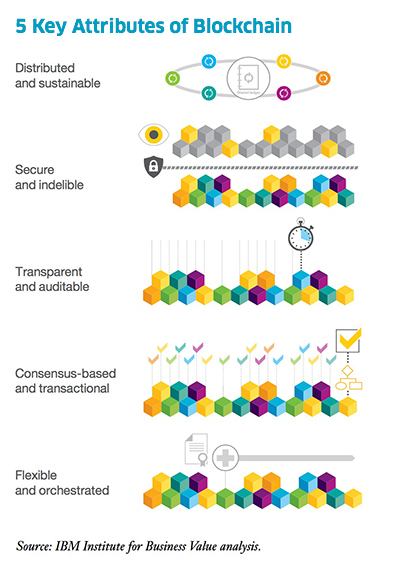

For example, in 2015 Leanne Kemp founded Everledger, a distributed public ledger for tracking the provenance of high-value assets, like diamonds. To date, Everledger has created a “multilayered digital fingerprint” of more than one million individual diamonds. The encyrpted information includes a serial number, 40 relevant integrity markers and the stone’s four-Cs (cut, color, clarity, and carat-weight). Once this data is embedded into the blockchain, the consensus nature of the technology prevents it from being altered, unlike paper and even server-based registries. Last year, hackers modified the color and clarity grades for more than 1000 stones logged into the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) database, inflating the value artificially. Kemp noted that not only can the blockchain technology prevent this kind of tampering, it also helps to establish the value of a diamond, by providing a chronology of ownership, custody, and location of the stone, from mining through ownership transfers.

“You cannot separate the value of an item from its origins and history,” she said. “When provenance is lost, risk emerges, and risk is the foundation of black market and counterfeit goods.”

Supply chain is second only to financial services as the most likely application for blockchain technology.

Blockchain Delivers

Another startup, Skuchain, is leveraging blockchain technology to develop supply chain apps for B2B trade and supply chain finance. Skuchain’s goal is to create a collaborative commerce platform that replaces paper-based transactions such as letters of credit and factoring, to give trading partners deeper visibility into their supply chain, enable smart forecasting decisions and be free from cash-flow constraints.

In conjunction with Commonwealth Bank, Wells Fargo, and Australian cotton trading firm Brighann Cotton, Skuchain recently facilitated what is believed to be the first cross-border commodity transaction traded and settled between unrelated global banks using blockchain. The transaction involved the purchase of eighty-eight bales of cotton from Texas, which were then shipped to Qingdao, China (and tracked via GPS), using the Skuchain distributed ledger to digitize all bill of lading information.

“You cannot separate the value of an item from its origins and history. When provenance is lost, risk emerges and risk is the foundation of black market and counterfeit goods.”

The transaction was a pivotal step in the application of smart contracts. In a statement, Michael Eidel, Executive General Manager of Cash-Flow and Transaction Services for Commonwealth Bank, noted that existing trade finance processes are “ripe for disruption” and this proof of concept demonstrates how companies could benefit from these emerging technologies.

“The interplay between blockchain, smart contracts and the Internet of Things is a significant development towards revolutionizing trade transactions that could deliver considerable benefits throughout the global supply chain,” said Eidel.

Story Telling

As players like Skuchain and Everledger work to methodically build the business case for blockchain in the supply chain, others are jumping into full-on disruption mode.

In October, members of the Ethereum community introduced the “Genesis of Things,” an open platform for the 3D printing supply chain. Genesis of Things combines 3D printing, blockchain, and IoT in “a virtuous, futuristic flow that re-imagines manufacturing processes,” the company reports. Creating a pair of 3D printed cufflinks as an example, Genesis of Things has embedded a mass customized binary serial number on the side of the cuff links that contains all the information on the manufacturing process and design of the cufflinks. Then this unique identifier is anchored into the blockchain.

“Design files are the crown jewels of 3-D manufacturing value chains, and must be extremely well-protected against theft or tampering when shared among a global network of printing facilities,” according to a recently released report white paper from Cognizant entitled How Blockchain Can Slash the Manufacturing “Trust Tax.”

“The creation of a decentralized, transparent database of rights makes it possible to associate smart contracts and price agreements with a 3D printable design.”

Carsten Stöcker, co-founder of Genesis of Things and co-author of the Cognizant report adds, “Every product has a story: where it came from; how it was made; and how it is used. With Genesis of Things, the story is now revealed for all to know.”

The creation of a decentralized, transparent database of rights makes it possible to associate smart contracts and price agreements with a 3D printable design. So, whenever a device with their registered design is produced, the rights owner will receive automatic royalty payments via smart contracts.

The technology also holds tremendous potential in the high-tech sector for the support of obsolete components. With the manufacturing process recorded into the product code, each new part produced is guaranteed to meet the exact specifications as the original.

Find Your Fit

Still, the million dollar question for supply chain practitioners is whether blockchain is something they need to be thinking about now. It’s important to note that many of the more conservative views of blockchain potential tend to involve the FinTech sector, where regulations and generations of legacy processes tend to repel change like water off a duck’s back. When it comes to supply chain applications, the conversation is generally positive.

The Cognizant report concludes: “While all the elements required to deliver blockchain-enabled ‘distributed trust’ supply chains are not yet in place, it’s essential to begin experimenting now by funding targeted proofs of concept to explore where and how blockchain thinking and technology could deliver transformative benefits…We recommend that manufacturers aggressively proceed with proofs of concept in selected areas such as 3-D printing, where the benefits of low-cost distributed trust are a particularly good match for the benefits of blockchain.”

There is no doubt that the hype around blockchain has reached a fevered pitch, but as the late, great American boxer Muhammed Ali once said, “it’s not bragging if you can back it up.” Blockchain may not solve all the world’s problems, but with growing support from industry giants like Microsoft, IBM, Walmart, Intel, and SAP, it is a technology with vast potential that companies should not underestimate.

Related Resources:

- White Paper: How Blockchain Can Slash the Manufacturing “Trust Tax”

- Article: Blockchain technology is on its way to becoming a universal supply chain operating system

- Organization: The Blockchain Alliance

- Article: Fujitsu reportedly developing blockchain-based technology to produce a tech-savvy method of safely and securely handling confidential data

- Article: Five Applications for Blockchain in Your Business

- Report: Blockchain – Enigma, Paradox, Opportunity

- Report: Blockchain for the Supply Chain: 15 SCtech Players to Watch

- Infographic: Blockchain Use Cases