Nike Takes the Leap

Unique deal gives Nike instant infrastructure in the Americas

From the moment Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman hijacked his wife’s waffle maker to create Nike’s first grooved-sole sneakers in 1971, the Nike brand has been synonymous with innovation and high-performance athletics. Just as its product focus has remained steadfast on delivering footwear and sportswear designed to help athletes reach their full potential, Nike leadership has concentrated on keeping the company in peak form, innovating products, processes and technologies to serve the market where it is and where it is going.

With consumers’ “buy now, wear now” expectations and growing affinity for product personalization continuing to drive manufacturers to innovate faster and scale more effectively, the worldwide market is increasingly going local. Long, global supply lines built on the pursuit of cheap labor are no longer in tune with the demands of the market, according to Andrew Postal, managing partner of MMG Advisors. Once a strategic advantage, offshoring production to one region to fulfill demand in another distant location has become a competitive handicap, rife with inventory risk, hidden costs and sustainability challenges.

“Long, global supply lines built on the pursuit of cheap labor are no longer in tune with the demands of the market.”

Vertical Takeoff

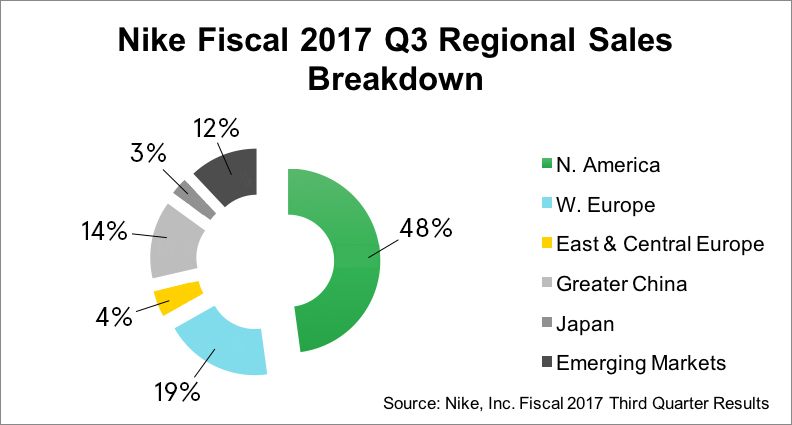

With nearly 50 percent of its $35 billion business coming from the Americas, but only 15 percent of its sourcing originating in the region, it was clear Nike needed a stronger presence in the West. The decision to transfer a portion of its massive manufacturing and assembly capability from Asia to locations within North and Central America put Nike among a growing cadre of multinationals, including General Electric Co., Ford, Wal-Mart Stores Inc., committing to boosting in-region manufacturing. But, true to form, Nike hasn’t followed conventional nearshoring routes. Instead, Nike’s journey has become a study in disruptive sourcing, featuring a revival of the vertical supply chain model – with a twist.

Nike’s nearshoring effort was complicated by the fragmented and generally underdeveloped condition of the apparel supply chain in the Americas, according to a company spokesperson. Many of the suppliers Nike would need to engage with were small and lacked the capital resources to scale and modernize to meet Nike’s stringent demands for quality and speed, Postal explained. With neither the time nor inclination to nurture a new end-to-end supply network on its own, Nike opted to outsource much of the regional supply chain to Apollo Global Management, a private equity firm based in NYC. This is where things get interesting.

Apollo’s Mission

Exact terms of the agreement were not disclosed, but the bottom line is that Apollo, through its Special Situations I fund, will build and manage a vertically integrated supply network for the sports apparel market in the Americas, finance new manufacturing plants, warehouses and logistics networks, as well as acquisitions of textile and apparel suppliers in North and Latin America.

Establishing a comprehensive, Americas-based supply chain ecosystem, linking industry players including textile manufacturers, garment producers, embellishment, distribution and logistics will enable Nike to bring product creation closer to the consumer, enhance labor productivity, reduce materials waste and accelerate innovation. The deal, as announced, does not require Nike to make a capital investment in the new venture, but assumptions are that a core condition was assurance from Nike that there was going to be sufficient demand to warrant Apollo’s sizeable investment.

“Nike’s journey has become a study in disruptive sourcing, featuring a revival of the vertical supply chain model – with a twist.”

By the time the agreement was made public in August 2016, Apollo had already quietly launched the new umbrella organization, Tegra Global. They also acquired two existing Nike suppliers: New Holland Apparel, a full-service apparel manufacturer, based in New Holland, PA., with a Product Creation Centers in Honduras and Nicaragua; and ArtFX, Inc., an embellishment, warehousing and logistics operator from Norfolk, VA with a screen printing, embroidery and sublimation affiliate in El Salvador known as DecoTex International.

While Tegra CEO Steve Cochran told SCN that he cannot comment publicly about the company’s operations at this time, Tegra’s web site relates a lofty mission: “We’re changing the face of manufacturing stitch by stitch … We’re doing this by keeping merchandise in the Western Hemisphere and building supply chains that don’t waste capital. Instead, we consolidate resources, remove fragmentation, integrate vertically, and create quicker product turnarounds.”

One Giant Step

The New Holland and ArtFX deals, while significant, are not the culmination of the Nike/Apollo partnership; they are simply the first step, according to MMG’s Postal. MMG was a financial advisor to New Holland and ArtFX in their negotiations with Apollo. “If you are going to build a true fast-run, nearshore supply chain that includes onshore capabilities, you need a vertical supply chain that runs from raw materials all the way through distribution. That means we can expect to see additional, significant deals to complete the supply chain.”

“The model Nike and Apollo have conceived has significant potential to enable organizations across multiple industries to fast track efforts to close the gap between supply and demand.”

Both Nike and Apollo declined SCN’s invitation to discuss the progress of the partnership, however, in Nike’s Q3FY17 earnings call, CEO Mark Parker credited “automation and being closer to market” for generating tens of millions of dollars in gains per quarter.

Whether or not this specific agreement can go the distance, industry insiders like Postal and Simon Ellis, program vice president, supply chain strategies, IDC, believe that the model Nike and Apollo have conceived has significant potential to enable organizations across multiple industries to fast track efforts to close the gap between supply and demand.

“The idea of a company partnering with someone who can enable some of those knowledge capabilities that have atrophied in the U.S. due to lack of demand, is quite interesting,” said Ellis. “You can certainly envision that this could assist companies in bringing manufacturing to the U.S.”