Intel: The Making of a Conflict-Free Supply Chain

How one powerful letter inspired Intel’s historic quest for a conflict-free supply chain

Gary Niekerk remembers when the letter crossed his desk about five years ago. It was unlike any other the Director of Corporate Citizenship at Intel Corp. had read. Signed by more than a dozen nonprofit organizations, it spoke of civil conflict and horrendous atrocities happening in and around the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

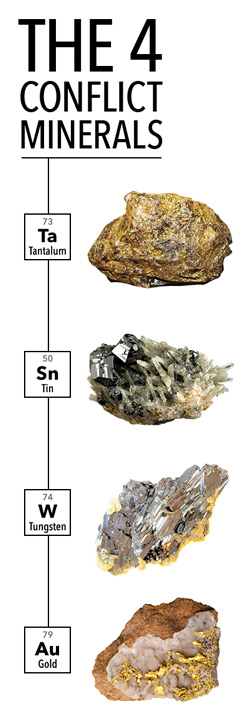

What grabbed Niekerk’s attention was the disclosure that proceeds from the sale of the region’s gold-, tantalum-, tin- and tungsten-producing ores (aka conflict minerals/3TG) were often diverted to armed militia who brutally victimized local women and children. According to the Enough Project, a non-profit group that fights to end crimes against humanity, the mines generate an estimated $185 million annually for terrorist groups. Companies like Intel that use these metals in their end products, the letter stated, could inadvertently be funding these terrorist groups.

What grabbed Niekerk’s attention was the disclosure that proceeds from the sale of the region’s gold-, tantalum-, tin- and tungsten-producing ores (aka conflict minerals/3TG) were often diverted to armed militia who brutally victimized local women and children. According to the Enough Project, a non-profit group that fights to end crimes against humanity, the mines generate an estimated $185 million annually for terrorist groups. Companies like Intel that use these metals in their end products, the letter stated, could inadvertently be funding these terrorist groups.

“This was an intense letter,” said Niekerk. “How do you even respond to a letter like this?”

For Intel, the response started with an in-person meeting in Washington, D.C. with representatives from the Enough Project. That meeting, and the information that came out of it, sparked a multi-year supply chain initiative that led to Intel’s groundbreaking announcement in January 2014 that it had became the first and only company in the electronics sector to offer conflict-free microprocessors. The next milestone for Intel: a fully conflict-free supply chain across its entire product portfolio by 2016.

The Journey

Intel’s journey to conflict-free has been wrought with tension and tough decisions. For instance, despite calls to boycott the DRC, Intel decided to keep using minerals sourced from central Africa while it built its conflict-free program. A boycott, the chipmaker believed, would severely damage the livelihood of too many innocents.

Intel’s first step was to survey roughly 75-100 key suppliers that were most likely buying 3TG and determine where the materials were sourced, said Niekerk. “We had a good idea of how the metals were used in our products. But we didn’t have a good idea of where those metals came from,” he said. “The vice president of our supply chain sent letters to all the suppliers who supplied products, parts or materials that contained these metals. We asked if they knew where their minerals were sourced from and if they had a policy to source or not to source from there.”

Despite calls to boycott the DRC, Intel decided to keep using minerals sourced from central Africa while it built its conflict‑free program.

The survey outcome was “unacceptable,” according to Intel CEO Brian Krzanich, who was COO at the time. Krzanich directed Niekerk and his team, which included now-retired Supply Chain Vice President Craig Brown, to “fix it.”

“He told us: ‘I want you to come back with a roadmap and a plan that is going to show me each of these metals and when I can expect to see these conflict minerals out of my supply chain. Don’t come back to me until you have this,’” recalled Niekerk. “We looked at each other and said, ‘How are we going to fix this? We can’t even track it.’”

The Fix

With this executive mandate, conflict minerals management became a top priority. To accelerate the effort, Niekerk suggested going straight to the smelters for the mineral data. “We have 16,000 suppliers in the world, but the number of smelters that interact with our supply chain is less than 200—that’s a manageable number.”

The team got permission to visit one smelter. This visit gave the team insight into smelting systems, how the operation worked, what information the smelter collected about their materials and what country or mine data they included on shipping manifests.

Getting access wasn’t always easy. As a downstream buyer, some suppliers didn’t feel there was a compelling reason to show Intel their books. Others simply wouldn’t let the Intel on the premises. “The smelter visits originally were a learning exercise. We wanted to see how the process worked. Then it became an exercise in convincing them to go through an audit,” he said. The conflict minerals program team, which is now headed up by Intel Supply Chain Director Carolyn Duran, has visited 88 smelters in 21 countries, said Niekerk.

The chipmaker, with the help of a task force it helped create through the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) and other associations, began developing “bag-and-tag” tracking programs and auditing protocols. It leveraged smelter and mining-related policies from the gold industry as well.

Slowly, some smelters agreed to third-party audits, but didn’t want to pay for it. The team went back to Intel’s senior management, via the task force, to the management of other leading companies, and asked for $400,000 to offset the auditing costs. The money was pooled into an Early Adopters Fund and was managed by a nongovernmental organization, Niekerk said. Smelters that passed the audit were listed with the EICC’s Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative group and information was shared across the industry. “The idea is to be transparent and let everyone know who the good smelters are,” he said. To date, a total of 106 smelters have been validated as conflict-free through the industry’s conflict-free sourcing initiatives.

As more companies choose to do business only with those smelters who source responsibly from the DRC, the profit motive for the armed groups controlling mines in the region is diminishing. A recent Enough Project report indicates that these armed groups are beginning to cede control of some of the mines.

Though conflict in the region is still far from being resolved, positive momentum is building. For its part, Intel remains focused on the next leg of its journey: all product lines conflict-free by 2016. When asked how the company would approach this new, even more ambitious goal, Niekerk laughed. “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. It’s the same thing here.”

Related Resources:

- White Paper: Intel’s Efforts to Achieve a “Conflict Free” Supply Chain

- Video: Conflict-Free Technology Panel Discussion, CES 2014

- Video: Chips, Conflict and the Congo – Gary Niekerk at TED@Intel (May 9, 2013)

- Website: EICC/GeSI Conflict-Free Smelter Program

- Website: Conflict Minerals Reporting Template

- Website: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas

- Blog: How Conflict-Free Minerals Are Advancing Human Rights