Is Corporate Hierarchy Undermining Your Digital Transformation Progress?

With the exception of the brilliant mission control engineers at NASA who famously saved the lives of the Apollo 13 crew by brainstorming a solution to make a square CO2 filter fit into a space designed for a round one, most of us learn at a pretty early age that as hard as we may try to jam that square peg into the round hole, it’s never going to fit right.

Yet, this is essentially what many businesses today are unwittingly attempting to do by deploying state-of-the-art digital technologies and processes within an old-school, top-down corporate model, according to a small-but-growing contingent of management thought leaders. These experts believe that the fundamental incompatibility between the linear, command-and-control bureaucracy that girds most corporations and the sense-and-respond agility these organizations are trying to achieve may explain why as many as 78 percent of enterprises are not realizing the full potential of their digital transformation efforts.

The fundamental incompatibility between the linear, command-and-control bureaucracy and the sense-and-respond agility organizations are trying to achieve may explain why many enterprises are not realizing the full potential of their digital transformation efforts.

In a 2018 report, Digital Supply Chain Leaders Must Move Beyond Organizational Hierarchies, Ken Chadwick, vice president of research at Gartner stated that that traditional hierarchical organization structures are too slow to address the needs of digital businesses. He recommended that enterprises “stretch their thinking toward a more adaptive organizational strategy.”

This is exactly what pioneering businesses like the eSteering business unit at Danfoss Power Solutions are doing by exploring ways to replace the traditional corporate hierarchy with new “flatter” organizational models that promote greater autonomy, empowerment and agility.

Since 2017, Vivek Menon, senior director of the eSteering, has been leading the effort to transition the eSteering group from traditional top-down hierarchy to a self-managed team model where “power” is distributed throughout the team, empowering individuals to operate with greater speed and agility.

“It’s time for companies to think differently not just about our products and services and how they are conceived and produced, but also about our business models,” said Menon.

To facilitate more organizational agility, teams within eSteering are organized into cross-functional, purpose-driven “circles,” each with their own purpose and accountabilities, as defined by Holocacy.org. Each team member’s roles reflect both their motivation and competency. “This enables the unleashing of the full potential of the team’s capabilities,” Menon explained. “For example, one of our test engineers is also a passionate photographer, so he gets involved making marketing videos for us. Typically, this wouldn’t be possible with static job descriptions and rigid role definitions.”

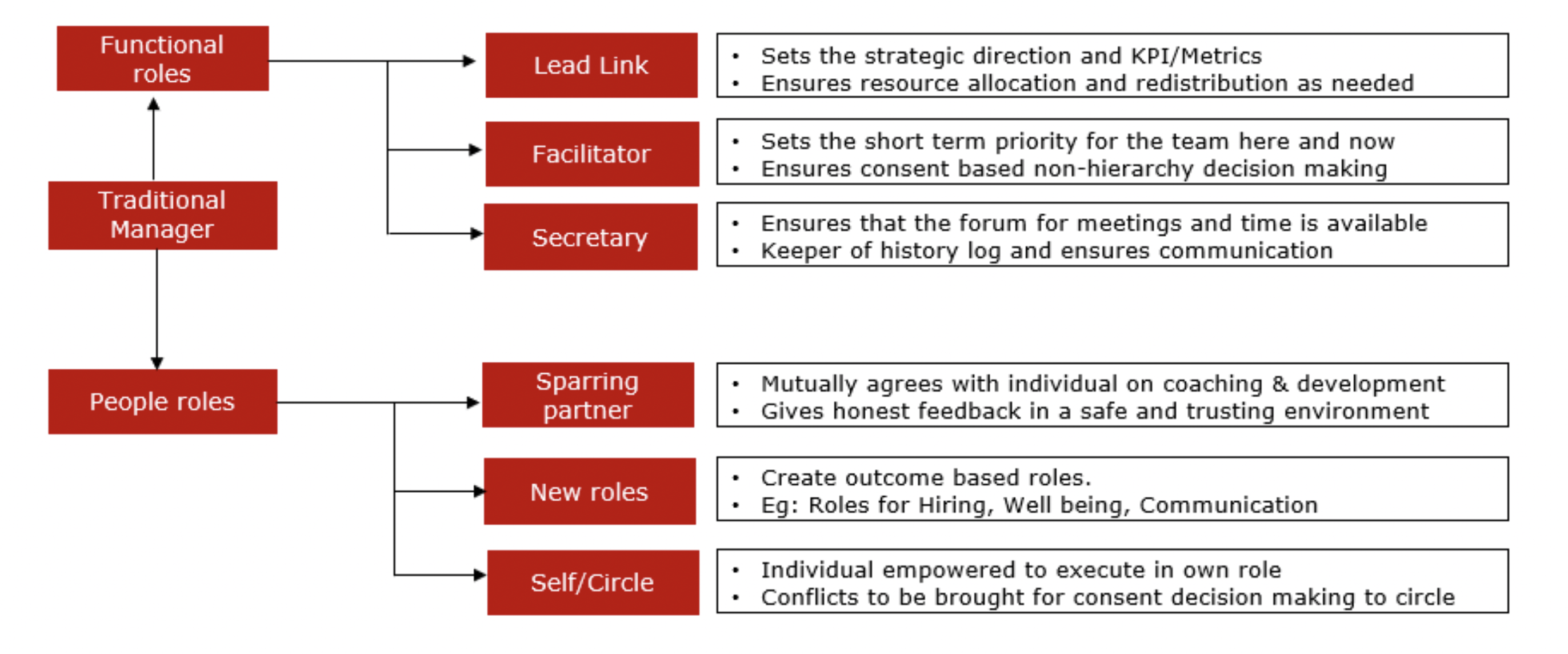

Not surprisingly, the most common question Menon gets asked about eSteering’s flat organizational structure is: how do you work without managers. To this, Menon replies, “No manager does not mean no management.” Taking cues from branded agile methodologies like Holocracy and Sociocracy 3.0, Danfoss split and decentralized the main functional accountabilities of the eSteering group’s managers into separate roles handling the “functional” and “people” responsibilities of a traditional manager [see e-Steering: How We Work Without Managers].

In this kind of distributed decision making model, “those who lead do so because people follow them, not because they have a title on their door,” according to renowned business advisor Chuck Blakeman.

eSteering: How We Work Without Managers

Fighting Inertia

Menon acknowledges that the toughest part of the transformation from hierarchy to self-management has been changing mindsets and behaviors, including deep-rooted aspects of decision-making accountabilities and formal and informal power structures. “This has to be coached, cajoled, pushed, pulled, celebrated, learnt from missteps and everything in between,” he said. “The natural inertia of change in any organization keeps trying to pull you back into hierarchy.”

This tendency to “pull back into hierarchy” was clearly demonstrated in a study done in the early 1990s by James Barker, then a professor at Marquette University. Barker conducted a three-year study of a local manufacturing company that had adopted a self-managed team model. What he found was that Max Weber’s theory of the “iron cage” of control was less a function of a bureaucratic constraints as it was human nature.

“Over time the organization’s members developed a system of value-based normative rules that controlled their actions more powerfully and completely than the former system,” he explained. For example, the teams not only spent an inordinate amount of time sorting through the various rules they had created around attendance, but they began monitoring each other’s behaviors.

“We naturally create these systems because we have to have some way of coping and managing within complexity.”

During one of this site visits, a technical worker at the facility related to Barker that he felt more closely watched now than when he worked under the company’s old bureaucratic system. “He said that while his old supervisor might tolerate someone coming in a few minutes late, his team had adopted a ‘no tolerance’ policy on tardiness.”

In the years since publishing his study, Barker, now chair in Business Education in the Rowe School of Business at Dalhousie University, has come to believe that the actions of the team reflect an instinctive human response to complexity. “We naturally create these systems because we have to have some way of coping and managing within complexity. This is just the way we do things.”

A more contemporary illustration of this predisposition was recounted in a 2019 Financial Times article Boss-less Business is No Workers’ Paradise which described the experience of a Berlin-based startup called Blinkist. The company’s founders had quit their corporate careers and wanted to “build a company of equals.” In less than two years, their “radical experiment” in self management quickly devolved, when despite their best intentions, a “pecking order” emerged. “The corporate hierarchy that we’d rejected, we’d recreated,” said co-founder Niklas Jansen.

These examples beg the question: Is it really possible to replace bureaucracy?

“Bureaucracy is constraining, but it is good at maintaining over time,” said Barker. “Humans have never created an organizational structure that endures better over time than bureaucracy. We don’t like it in many ways, but it does what it is supposed to do.” Still, Barker believes that more effective collaboration is essential for businesses today, and self-managed teams unquestionably enhance collaboration. “It’s a conundrum. The key is accepting that this tendency to tilt toward constraints is going to happen, so, we have to watch for it and then figure out what to do about it.”

“We have to ask ourselves, with all this technology, connectivity and talent, why is this not working?”

Despite the many challenges, experienced business transformation leader Bill Chambers has no doubt that the time is right for this fundamental transformation in how companies operate. “We are in the 4th Industrial Revolution, we have gone from computing to connectivity. We have more tools and digitization and information and connectivity available to us than ever before, yet on the whole businesses are less productive than they were 30 years ago. So, we have to ask ourselves, with all this technology, connectivity and talent, why is this not working? I have to believe that it is the organizational design that is constraining us.”